Displaced Rohingya People in Rakhine State.

Having been described by the UN Secretary-General, Antonio Guterres as “one of, if not the, most discriminated people in the world”[3], the Rohingya are one of several Myanmar’s ethnic minorities, however, amongst the mostly Rakhine-state-based population, the highest percentage of Muslims in Myanmar occurs [3].

Who are the Rohingya?

The Muslim minority, which presence in Burma, can be dated to 15th century [5], says that they are descendants of Arab traders, with their own language and culture, backing up their legitimacy [3]. Despite their centuries long presence in the country of mostly Buddhist, at times filled with violent nationalism, population of 54 million [6], the Rohingya are perpetually being denied citizenship (the 1982 “Citizenship Act” recognised 145 ethnic groups but the Rohingya amounting to the population of 1 million, at that time, were not recognised).

They officially became “stateless people” [5], with consequently, being stripped of the right to education and healthcare [6]. What is more, the minority has been excluded from the 2014 census, which means that the government refused to recognize them as a people [3]. The oppressed group, is seen as illegal immigrants, and interloops from Bangladesh [3]. This argument only makes sense in its geographical aspect, as the Rakhine state borders the People’s Republic of Bangladesh.

The tensions

The discrimination started more than 50 years ago, when the two conflict-stricken groups supported the opposing sides (the Rohingya sided with British colonialists, who ruled the country, and the Buddhists supported the Japanese invaders, hoping that they would help to end the British rule after the World War II) [5]. The recent wave of violence, followed by an army crackdown in 2017, leaves one in utter staggerness, which the Human Rights Watch called “an ethnic cleansing campaign” and the United Nations later described as a “textbook example of ethnic cleansing” [3].

The Human Rights Crisis

The latest crisis was sparked on 25 August 2017, when the Rohingya militant group – Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (ARSA) let coordinated attacks on more than 30 police posts[3], killing several officers [4]. In response, the Myanmar’s military, known as the Tatmadaw [6] ,and the clearance operations it exercised in the western state of Rakhine, prompted more than 730,000 people to flee Myanmar, mostly to Bangladesh, where they now live in the “squalid conditions in the world’s largest refugee camp”, the BBC reported. Albeit , the estimates of the numbers are hard to be verified [3]. “The United Nations’ Independent International Fact Finding Mission said in August 2018 that the army’s tactics were „grossly disproportionate to actual security threats” and that „military necessity would never justify killing indiscriminately, gang raping women, assaulting children, and burning entire villages.””, the BBC reports. Myanmar, constantly rejecting the UN report, said its operations targeted “militant or insurgent threats” [4]. According to a medical charity, Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), around 6,700 Rohingya were killed in a month (after the violence broke out) [3]. The government of Myanmar claimed that the “operations against militants” ended on 5 September, putting the number of dead at 400. However, the BBC claimed that its correspondents have seen evidence that the atrocities continued after that date [3].

Emergency food and shelter to help displaced Rohingya people, western Burma, 2012.

Despite being systematically refused entry to Myanmar, the investigators were able to gather testimonies from people who have fled the country. The crackdown was carried out with a “genocidal intent” as it was commented on by the UN investigators [13]. Both Myanmar, and the military have denied those accusations, as The New York Times reports. The army of Myanmar has, too, been accused of “mass murder, systematic rape and other abuse amounting to what the US Holocaust Memorial Museum describes as compelling evidence of ethnic cleansing, crimes against humanity and genocide”, [6]

A glimmer of hope

On 11 November 2019, The Gambia, which is not only, the smallest country on Africa’s mainland, but also 7,000 miles away from Myanmar, with little to none ties between the two countries, filed a case at the International Court of Justice (ICJ), thanks to the fact that every UN member state has equal standing in the ICJ [2]. The Gambia started talking about the Rohingya in May of 2018, when the Gambian Attorney General and Justice Minister, Abubacarr Tambadou, visited a Rohingya refugee camp in Cox’s Bazaar, Bangladesh, with a delegation from the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC).

The stories he heard from the refugees reminded him of the great deal of time he had spent on working as a prosecutor at the International Criminal Tribunal regarding the 1994 Rwandan Genocide [2]. “All that mattered, Ms. Maunganidze, who is the head of Special Projects and an Expert in International Criminal Justice at the Institute for Security Studies in South Africa, notes, was the strength of the case it assembled from UN reports and other investigations into the violence”. [2].

The plaintiff, motivated by the small Muslim-majority of its own, with the support of the 57-member (OIC) and a team of international lawyers, accused Myanmar of breaching its obligations under the 1948 Genocide Convention , to which both of the countries are signatories, and called for “the Court to order “provisional measures”” to prevent all acts that may amount to or contribute to the crime of genocide against the Rohingya and protect the community from further harm while the case is being adjudicated” [1]. Also, “In its filing, The Gambia asked the court to implement an injunction to make sure Myanmar immediately „stops atrocities and genocide against its own Rohingya people”, BBC reports. Having signed the convention, Myanmar was and is committed to “preventing and punishing the crime of genocide”, the BBC reports. However, the ruling on that main issue itself could be “years away”, The New York Times reports.

The process

Public hearings on “provisional measures” were held in The Hague on 10-12 December 2019. The defendant’s delegation, headed by the State Counsellor and de facto leader Aung San Suu Kyi (a Nobel Peace Prize winner), has perpetually denied the allegations of genocide, and urged the Court not only to refuse the request, but also reject the case. [1], [3]. “At the hearings, Ms. Aung San Suu Kyi heard gruesome accounts of summary executions, babies thrown to their deaths, mass rapes and whole villages burned to the ground.

When it was her turn to speak, she did not directly address those accusations, but told the court, ”Genocidal intent cannot be the only hypothesis.”, The New York Times reports. Not only did the Oxford educated Ms. Aung San Suu Kyi, was defending the same military which kept her under house arrest for 15 years, but also, most importantly, avoided the term “Rohingya” as it implies the group’s legitimacy as an ethnic minority. Most people in the Buddhist dominated country, call them “Bengalis”, in order to draw an analogy to the alleged Bangladeshi origins of the people. “She also said Gambia’s case against Myanmar was “precariously dependent on statements by refugees in camps in Bangladesh,” who she said “may have provided inaccurate or exaggerated information.”, according to New York Times.

Myanmar’s word against the world

On 20 January 2020, just days before the ICJ ruling came out, the Myanmar-established Independent Commision of Enquiry (ICOE) submitter its final report, regarding the events of 2017. “The Commission was neither independent nor impartial and cannot be considered a credible effort to investigate the crimes against the Rohingya. Meanwhile, there have been no efforts to investigate the serious and wide-ranging violations against other ethnic minorities or elsewhere in the country”, said Amnesty International.

The so-called “Independent” Commission of Enquiry reportedly found no evidence of “genocidal intent” in the military’s actions. “War crimes, serious human rights violations, and violations of domestic law took place during the security operations,” the commission said. It reported there was evidence that the security forces were involved in several mass killings of civilians, which may have claimed the lives of as many as 900 people.”, according to the New York Times.

The ruling

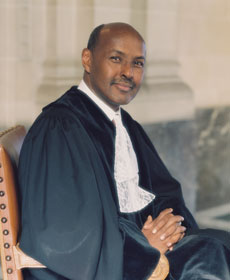

Just a few days later, the Court headed by Judge Abdulqawi Ahmed Yusuf of Somalia, ruled in The Gambia’s favor on 23 January 2020. The ICJ, which normally rules on disputes between states, opposing to the ICC, which can try individuals accused of war crimes or crimes against humanity (the body approved an investigation into the case, despite Myanmar not being the member of the ICC [3]) ordered Myanmar to take action to protect the Rohingya from “the acts of genocide, including killing causing causing serious bodily or mental harm, or deliberately imposing conditions meant to bring about the destruction of the Rohingya population” [6].

Just a few days later, the Court headed by Judge Abdulqawi Ahmed Yusuf of Somalia, ruled in The Gambia’s favor on 23 January 2020. The ICJ, which normally rules on disputes between states, opposing to the ICC, which can try individuals accused of war crimes or crimes against humanity (the body approved an investigation into the case, despite Myanmar not being the member of the ICC [3]) ordered Myanmar to take action to protect the Rohingya from “the acts of genocide, including killing causing causing serious bodily or mental harm, or deliberately imposing conditions meant to bring about the destruction of the Rohingya population” [6].

Despite the order being provisional, the Myanmar authorities must comply with the Court’s ruling to preserve, and prevent the destruction of, any evidence, especially the ones connected to the allegations of genocide, and to cease violations against the community. The court also ordered Myanmar to report back within four months, of the ruling, on what steps has it taken, with reports appearing constantly every 6 months “as long as the case remains open”.

The decision, despite being a small step of the journey that lays before the whole of international community, is historic. Obviously, it is important because of the message the filing, the case, and the process holds, but also for the first time in the history of ICJ “the plaintiff wasn’t a nation connected to the crimes it said were committed”, [2]. “This case could serve as a precedent for forcing states to take action on genocide,” Ms. Maunganidze told the CS Monitor 2 Establishing this king of precedents is crucial, as it helps the now international law to develop [OPINION].

The defendant’s response

Myanmar rejected the ruling in a statement from its Foreign Affairs Ministry. “The unsubstantiated condemnation of Myanmar by some human rights actors has presented a distorted picture of the situation in Rakhine,” The New York Times reports. The army in Myanmar (formerly Burma) consequently denies targeting civilians, which immediately denies the accusations of genocidal intent being at the military’s hearts.

What will be changed?

“The chances of Aung San Suu Kyi implementing this ruling will be zero unless significant international pressure is applied,” said Anna Roberts, executive director at the Burma Campaign UK.

Because of the military-government-newly-ratified Constitution of 2008, the power of a civilian leader, in this case Ms. Aung San Suu Kyi, is severely limited. The only way to bypass the disadvantageous position of hers, in the upcoming elections, at the end of 2020, was to shore up support, and turn away the public’s attention from the poor economic performance of her party, with her “dramatic… appearance at The Hague”.

“You might see the critics of Aung San Suu Kyi on Twitter because international communities are mostly on Twitter. But on Facebook, most people support her and I’m sure her party will win again in coming elections. I feel that she is the real mother of our country.” said Ko Win Hlaing, a taxi driver, for The New York Times.

The recent internet shutdown; a coincidence or perfect timing?

On February 3, 2020, the Norwegian Telenor Group issued a statement, on its website, that the Myanmar Ministry of Transport and Communications has directed “all mobile operators in Myanmar to stop mobile internet traffic for up to three months in five townships in Rakhine and Chin States”, Forbes Reports. RightsCon Brussels defines Internet shutdowns as “intentional disruption of internet or electronic communications, rendering them inaccessible or effectively unusable, for a specific population or within a location, often to exert control over the flow of information” [9].

It is crucial to know that the five townships have already been subjected to data network shutdown from 30 June to 31 August, 2019. “The Myanmar Ministry of Transport and Communications has been relying on the arguments of security and public interest to justify the directive”, says Forbes. In September of 2019, the Human Rights Council called on the government of Myanmar to restore the internet and revoke the Section 77 of the Telecommunications Law, which gives the Ministry of Transport and Communications overly broad powers, where the restrictions of any service do not have to be judiciary approved, and reserved for “exceptional circumstances”. [10]

Whereas in some parts of the world, Internet shutdowns are used as a means to controlling the society, the timing of the shutdown in Myanmar cannot be seen as a coincidence. As Human Rights Watch says, the shutdown will “make it harder for civilians to obtain help when needed, and significantly more difficult for humanitarian agencies to assist vulnerable populations”. “The shutdown in Rakhine state should not be seen in a vacuum but in light of the atrocities perpetrated in the state, including the atrocities perpetrated against the Rohingya Muslims”. In a joint statement, the UN experts, severely criticised the doings of Myanmar’s government, and called to, “lift its restrictions and grant [the people] immediate access to the media, humanitarian organizations and human rights monitors”. [8]. “The blanket suspension of mobile internet cannot be justified and must end immediately,”, the statement also said.

A decision from the other side of the globe

The Rohingya’s prospects for peace were once more disturbed, this time by the 45th President of the United States, Donald Trump.

The infamous “travel ban”, from the 21 February, includes the newly added Myanmar, amongst countries such as: Nigeria, Sudan and Tanzania. „Somebody in this administration probably realised that this is among the largest refugee population in the world,” said Mr Azeem Ibrahim, director of the displacement and migration programme at the Centre for Global Policy. „So if you want to stop refugees, you’re going to include one of the largest populations.”, he added. Not to mention, the illiteracy rates between the refugees are staggering.

Alexandra Iwanowska

[1] https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2020/01/myanmar-world-court-orders-myanmar-protect-rohingya/

[2] https://www.csmonitor.com/World/Africa/2020/0213/Rohingya-ruling-How-a-tiny-African-country-brought-Myanmar-to-court

[3] https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-41566561

[4] https://www.bbc.com/news/world-45341112

[5] https://youtu.be/04axDDRVy_o

[6] https://www.nytimes.com/2020/01/23/world/asia/myanmar-rohingya-genocide.html

[7] https://www.arabnews.com/node/1631176/world

[8] https://news.un.org/en/story/2020/02/1057651

[9] https://www.forbes.com/sites/ewelinaochab/2020/02/07/myanmar-shutting-down-internet-as-a-means-of-curbing-human-rights/

[10] https://www.amnesty.org/download/Documents/ASA1618052020ENGLISH.PDF