Maximilien François Marie Isidore de Robespierre was a French lawyer and statesman, best known for his incredible influence on the French Revolution. Maximilien Robespierre is best known as the principal figure behind the Reign of Terror, a period of radical revolutionary activity in France during which thousands were executed for “crimes against liberty”.

Involvement in the Revolution

Robespierre’s political affiliations varied – he was part of the Jacobin Club, the National Convention and the Committee of Public Safety, all of which played a pivotal role in French politics. As a member of the Constituent Assembly and the Jacobin Club, he advocated for universal manhood suffrage and the elimination of both clergy celibacy and slavery. In 1791, Robespierre became a vocal advocate for male citizens who lacked political clout, arguing for their unfettered entry to the National Guard, public offices, and the right to use arms in self-defense.

Robespierre was a prominent figure in the agitation that led to the overthrow of the French monarchy on August 10, 1792 and the formation of a National Convention.

His goal was to create a unified and indivisible France, equality before the law, the abolition of prerogatives, and the defense of democratic principles. Robespierre remains controversial to this day and is subject to much debate, mainly about whether he was embracing the principles of Enlightenment or a megalomaniac with a thirst for blood.

Head of the Jacobin Club

The Jacobin club gave Robespierre a voice in politics, even when he wasn’t part of the Legislative Assembly. His opposition to war with Austria and attacking of Girondin politicians made him stand out, and he was elected to the National Convention as soon as the monarchy was abolished. Through his speeches at the Jacobin Club, he was able to incite powerful insurrections such as the September Massacres, etc.

The Jacobin club gave Robespierre a voice in politics, even when he wasn’t part of the Legislative Assembly. His opposition to war with Austria and attacking of Girondin politicians made him stand out, and he was elected to the National Convention as soon as the monarchy was abolished. Through his speeches at the Jacobin Club, he was able to incite powerful insurrections such as the September Massacres, etc.

Robespierre proposed for the construction of a sans-culotte army to enforce revolutionary legislation and flush out any counter-revolutionary conspirators in April 1793, prompting the armed insurgency of May 31–June 2, 1793. The insurgency resulted in the eradication of the Girondins as a political force, further solidifying Robespierre’s power.

The Reign of Terror and the Committee of Public Safety

On 27 July 1793, Robespierre was admitted to the Committee of Public Safety, an organ of the government, created with the role of helping govern during a time of emergency. By now, the committee had largely overtaken the National Convention, and Robespierre emerged as the leader; Even though he was officially a member like everybody else, his reputation and national prominence allowed for him to single handedly steer the direction of the committee’s policies, creating the Reign of Terror.

The Reign of Terror was a period in the French Revolution when people were executed en masse for fear of being counter-revolutionary conspirators, organised by the Committee of Public Safety, of which Robespierre was a leading member.

On 10 June 1794, The Law of 22 Prairial, allegedly written by Robespierre, was passed. The law sought to simplify the judicial process at the Revolutionary Tribunal, amping up the bloodshed as a result. This is probably the reason as to why Robespierre is remembered as a tyrant.

Robespierre also used the Committee of General Security, a form of secret police, as a tool to criminalise even more people. Eventually, the two Committees would clash as a result of their responsibilities overlapping and Robespierre wanting the Committee of General Security to be subordinate, resulting in his downfall.

Cult of the Supreme Being

Although he was no fan of Catholicism, Maximilien Robespierre disapproved of the lack of a deity in the Cult of Reason because he thought gods were important to instill social order. Robespierre gave a strong denunciation of the Cult of Reason and its supporters in late 1793, before presenting his own view of a genuinely Revolutionary religion. The Cult of the Supreme Being, designed almost entirely by Robespierre, was approved as France’s civic religion by the National Convention on May 7, 1794.

Robespierre used the fiasco to publicly condemn the motives of many radicals who were not onside, and it resulted in the executions of Revolutionary de-Christianisers like Hébert and Danton, either directly or indirectly.

The establishment of the Cult of the Supreme Being marked the beginning of the reversal of the previously favored de-Christianization process. At the same time, it marked the pinnacle of Robespierre’s power.

Fall of Maximilien Robespierre

Robespierre mentioned internal enemies and conspirators within the Convention and the governing Committees in his speech on 8 Thermidor. He refused to name them, which alarmed the deputies, who were concerned that Robespierre was planning another purge of the Convention.

Robespierre mentioned internal enemies and conspirators within the Convention and the governing Committees in his speech on 8 Thermidor. He refused to name them, which alarmed the deputies, who were concerned that Robespierre was planning another purge of the Convention.

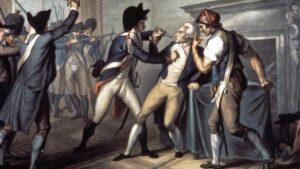

Because of the tense atmosphere in the Convention, Jean-Lambert Tallien, one of the conspirators mentioned by Robespierre in his denunciation, was able to turn the Convention against him and have him arrested the next day. By the end of the next day, Robespierre was executed in the Place de la Revolution, where King Louis XVI had been executed a year before. He was executed by guillotine.

Legacy

Robespierre’s opponents accused him of wielding dictatorial power in both the Jacobin Club and the Committee of Public Safety. His egalitarian ideas were condemned by counterrevolutionaries and the wealthy, while popular militants accused him of being too timid. His memory was relentlessly attacked after his death, and many of his papers were destroyed. Throughout history, he has been portrayed as either a bloodthirsty monster or a timid bourgeois.

Philip Forinton, DP1