On a sunny Saturday in New York, after a dramatic match, the Japanese tennis player Naomi Osaka won the 2018 US Open final. It was a great revelation, with her facing off the net game legend Serena Williams; however, not all fans celebrated with her on that day. In Japan, the country in which she was born and in the culture of which she was raised, by some she was not considered a worthy national representant.

In the recent years, the discussion on who can be a Japanese citizen has been on the rise. It comes as the percentage of mixed race or multinational families is surging.

Under the current law, at the age of 22, anyone who formally possesses another nationality has to choose which one to keep. Osaka herself faced the issue, picking to represent Japan in the following Olympics. By no means she is an isolated example; though, she has the privilege of being a famed and recognised figure.

The history behind the modern issues

The myth of Japan as a racial and ethnic monolith has been upkept since its restoration as a monarchy in 1868. It was rooted in the previous isolationist Sakoku policy, which for centuries kept the contact with non-Japanese individuals minimal. However, once the borders were opened, the influx of foreigners slowly rose, fuelled by the imperialist attempts to conquer Taiwan, the Ryukyu Islands, and Hokkaido (nowadays one of the main Japanese islands).

The myth of Japan as a racial and ethnic monolith has been upkept since its restoration as a monarchy in 1868. It was rooted in the previous isolationist Sakoku policy, which for centuries kept the contact with non-Japanese individuals minimal. However, once the borders were opened, the influx of foreigners slowly rose, fuelled by the imperialist attempts to conquer Taiwan, the Ryukyu Islands, and Hokkaido (nowadays one of the main Japanese islands).

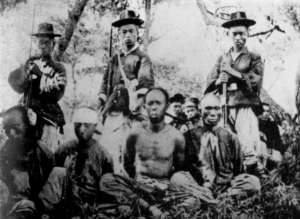

Subsequently, the wars with China and Korea came, during which many captives were kidnapped and brought to Japan as slaves. These rather atrocious practices directly impacted the numbers of the people of non-Japanese descent, already making the society not as homogenous as some would wish.

In the first half of the 20th century, the problem only grew more prominent, as more territories were conquered by the Empire of Japan. Moreover, the forced migrants had children too, many descendants of which still live today.

During the American occupation and the period of postwar growth, the number of economic immigrants of all races started rising as well. Nonetheless, throughout that time, the governments simply ignored the issue and the difficulties faced by those people, maintaining that Japan is ‘ethnically pure’.

So, who even is an ‘ideal’ Japanese citizen?

With the idea of homogenous Japan, it was rather easy for the people to start to conceptualise which traits are acceptable for Japanese citizens to have and which are not. Although personality and other non-perceivable aspects come into play, as exemplified by the widely present queerphobia, the bias primarily lies on appearance and accent. Thus, the deep connection of the matter to the issue of race – in terms of all: white, those ethnically Asian and, especially, people of colour.

While the typical white traits such as pale skin or big eyes are idealised and often fetishized, if one looks more East Asian, they will be perceived as inferior and automatically non-Japanese even if raised in that culture. Some so-called race theorists have even suggested that the inhabitants of Japan are genetically unrelated to other Asian communities, a view that is simply contradictory to science.

The bias against darker-skinned individuals is the most prominent, however. They not only face the systemic racism, but also often not fit into the Japanese beauty standards and thus are stigmatised.

What applies to all coming from a mixed background, is the label hāfu – derived from the word ‘half’. A part from intensely highlighting the mixed-race aspect, it also suggests that such person is not fully Japanese and may never be; thus, the term should be considered particularly harmful. It is often uncritically assumed that the people of multinational ancestry do not comply with the cultural norms, commit crime or even spy. At the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Japanese government and the media tied to it famously proclaimed it was the foreigners, targeting principally those of partial or non-Japanese ethnicity, responsible for the spread of the virus.

Everyday discrimination

Studies have shown that people of partly or fully foreign ancestry experience tremendous housing inequality – with the 90% of those rejected being of such origin, according to the mass survey conducted by the Ministry of Justice. Those who face the strongest discrimination are of non-Japanese Asian descent or have darker skin tone. A similar bias can be seen in regards to employment, as individuals looking not-Japanese-enough or who have a foreign surname experience severe difficulties with application refusal. It is automatically assumed that they do not know the language and would not be able to cooperate in a Japanese workspace environment.

Studies have shown that people of partly or fully foreign ancestry experience tremendous housing inequality – with the 90% of those rejected being of such origin, according to the mass survey conducted by the Ministry of Justice. Those who face the strongest discrimination are of non-Japanese Asian descent or have darker skin tone. A similar bias can be seen in regards to employment, as individuals looking not-Japanese-enough or who have a foreign surname experience severe difficulties with application refusal. It is automatically assumed that they do not know the language and would not be able to cooperate in a Japanese workspace environment.

This does not even account for the everyday racism experienced by those looking different. Various black people, including Naomi Osaka, have spoken out about the xenophobia they face. On the streets, they might be pointed at, have random passers wanting to take pictures of them or be touched without consent.

The relationship of Osaka’s parents for years was not accepted by her Japanese family due to the Haitan origin of her father.

The Future

Fortunately, it seems that the Japanese society is gradually undergoing a positive change. With more and more diverse residents, people are becoming more conscious and accepting; something largely prevalent in the youngest generation. Owing to the individuals such as Naomi Osaka, who openly speak out about the severity of the issue, even the government seems to start acknowledging the matter. Nevertheless, it is still a long way and, as long as more systemic changes are not undertaken, the question of who can be Japanese will still be pondered.

Jan Dobkowski, DP1

Sources:

Okraszewski, Maciej “Czy Japończyk może mieć inny kolor skóry” Dział Zagraniczny podcast, January 21, 2021.

Huang, Tiffany. Black in Asia. Spill Stories, 2020.

Wikipedia contributors, „Naomi Osaka,” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia,

https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Naomi_Osaka&oldid=1058701100

(accessed December 12, 2021).

Wikipedia contributors, „History of Japan,” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia,

https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=History_of_Japan&oldid=1058839915 (accessed December 12, 2021).

“Housing Discrimination against Foreigners in Japan: Ministry of Justice Survey.” Blog, May

18, 2017. https://resources.realestate.co.jp/living/housing-discrimination-against-foreigners-in-japan-ministry-of-justice-survey/.

Margolis, Eric. “What’s behind Housing Discrimination in Japan?” The Japan Times, June 2, 2021. https://www.japantimes.co.jp/community/2021/05/31/how-tos/housing-discrimination-still-problem-japan/.