Women’s Rights Movement, also called the Women’s Liberation Movement (WLM), was part of the “second wave” of feminism and a historically crucial social act. Unlike first-wave feminism, which involved suffragettes fighting for women’s legal rights such as the right to vote (as late as in the late 19th to early 20th century), the Women’s Liberation Movement is often regarded as ‘diverse’ because of the wide range of different aspects of women’s lives that were brought up by it.

Second-wave feminists

Second-wave feminists demanded equality in the areas of politics, work, the family, and sexuality, in opposition to prevailing social attitudes which favoured traditional gender roles in every one of these fields. Even though the end of World War II allowed for the service sector to develop, including several jobs unrelated with pure physical strength, and specialised technology evolved making housekeeping easier and less time-consuming, it remained the expectation that women stay at home.

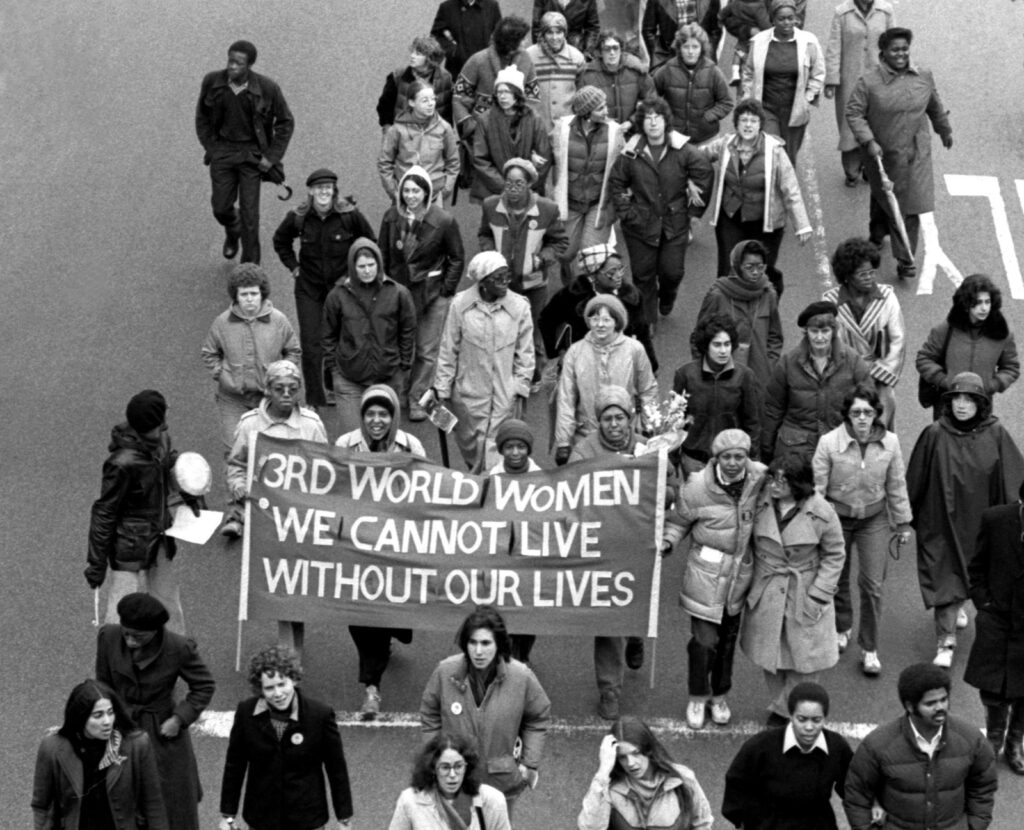

Dissatisfaction having grown among many women, they went out to the streets, joining together in massive and impressive protests around the country. The demands included immediate passage of the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA), granting equality of rights to all people regardless of sex, as well as increased access to contraception and abortion. It is often said about the movement that it brought together “women of all ages”, as it certainly did. What it had missed, however, were the long-struggling women of colour.

Multilateral discrimination

Racial equality was not on the agenda of the National Organization for Women (NOW) or others. Specifically, Black women, who were just then gaining platform and publicity, where being consistently told that the feminist movement is not about race and that too many postulates cannot be thrown at the government if the movement is to be taken seriously. At the end of the day, it was being said, the movement included all women, regardless of their race or sexuality (the LGBTQ+ women also argued that their needs and experiences were being omitted).

The problem with such confidence was and remains to this day, that women who are not white and straight, or either of those, are not only discriminated against because they are women. They experience a multilateral kind of discrimination, called intersectionality – for Black women, it is the intersectionality of racism and sexism. If these women are to be included in a movement advocating women’s rights, feminism must be just as class- and race-conscious as it is gender-conscious. And until recently, it was not.

Middle-class feminism

First, the suffragists openly and successfully prevented Black women from joining, with their leader Susan B. Anthony infamously saying:

“I will cut off this right arm of mine before I will ever work or demand the ballot for the Negro and not the woman.”

Later, in 1963, Betty Friedan wrote The Feminine Mystique which is considered one of the most influential feminist pieces. Only recently has Friedan been recognised as racist and classist in her nevertheless noble and inspiring writing. It has been understood that The Feminine Mystique, while successfully summarising the fundaments of feminism, represents the plight of middle- or upper-class, educated, married white women, who, bored with serving as housewives, demanded freedom and opportunity to take up new jobs. As Black feminist theorist bell hooks (Gloria J. Watkins) wrote in her book From Margin to Center;

“She (Friedan) did not discuss who would be called in to take care of the children and maintain the home if more women like herself were freed from their house labor and given equal access with white men to the professions”.

Second-wave feminists, under the cover of erasing race to regard all women as ‘equals’, notoriously disagreed to include Black women’s demands which addressed class- and race-based discrimination in workplaces, politics, and households (in the US class and race are usually closely intertwined). Moreover, the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s to 60s, which advocated equal rights for African Americans, focused exclusively on the oppression of Black men, and Black women have even experienced sexism within the structures of that movement.

Black feminists’ organizations

Black feminists to this day tend to ask “how can we become the agenda” instead of “how can we get on the agenda” because they understand that the system, as it is currently structured, will never address them or give them deserved credit – fundamental changes on the institutional level must be implemented. They clearly point out that what Black women are entitled to is not equality in the unfair system, but rebuilding the system so that it never questions anyone’s rights and abilities based on their gender, race, sexuality, or any combination of those.

Emilia Juchno, IB2