„Price of Inequality” by Joseph Stiglitz, Nobel prize recipient for his contribution to theory of asymmetric information (situation when buyer knows more than the seller of a product or seller knows more than the buyer), focuses on appallingly growing inequality in the US, the most unequal country in developed world. The problem, though, is not restricted to the US but concerns the globe all over, to a larger or lesser extent. Perhaps the biggest problem with reducing inequality is that inequality is like a vicious cycle – it is cause and consequence of the failure of political system, which contributes to the failure of economic system, which in turn contributes to increased inequality.

Economic and social consequences of rising inequality

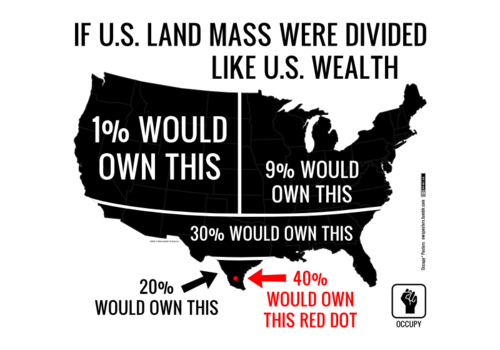

As the researches have shown, major determinant of individual’s success are their initial conditions – the income and education of their parents. For a family, lack of wealth means inability to invest in their children which on a large scale results in underinvestment in human capital. It would be far from plain sailing, but still easier than it is in current state of affairs, to justify inequality if the amount money which is lost to the bottom would be equal to the amount of money which is given to the top. In fact, it would be Pareto efficient (in other words, no money would be lost in the process of redistribution). But today’s system of redistributing, reinforced by regressive taxation, money is characterized by terrific allocative inefficiency – the gains to the top are far less than the losses to the bottom – largely due to law of decreasing marginal return (1000$ is far less important for Bill Gates than it is for a poor mother of 5 kids). Together, all this results in lower growth, higher level of poverty (with all its social and economic consequences, like loan defaults, alcoholism, depression etc), political instability, weakened democracy and a diminished sense of fairness and justice.

Causes of rising inequality: should we blame innovation and globalization, or rather regulation and policy-makers?

There are at least several causes for growing inequality. Firstly, in the second half of 19th century, “marginal productivity theory” came to dominate in economic circles. It said that those with higher productivity have greater contribution society, so they should be rewarded. Through laws of supply and demand, incomes will be determined – those with rare, valuable skills will earn more than idle or underskilled people. Experience has shown, though, that this is not the case with, for instance, CEOs in huge corporations in the US who on average earned (in 2010) 243 times more than typical workers.

Technological change and globalization, with all their positive effects, also had a say in increasing inequality. In the last 30 years, computerization enabled machines to replace jobs that could be routinized. This increased demand for those who mastered modern technology and (drastically) reduced demand for those for who were substituted with computers and machines. Globalization reinforces this trend because the jobs that can be routinized are outsourced.

This leads to another cause of increasing inequality – so-called “polarization of the labour force”. Jobs which cannot be easily computerized (nursing, cleaning) fall into the category of low-paying jobs. Middle-income jobs, which used to exist mostly in manufacturing, have been destroyed by computerization and globalization. Jobs at the top, mostly in the financial sector (large majority of both 10% and 1% of richest Americans are bankers), thrive – when it comes to wages – but are extremely scarce relatively to the size of population. So the results of polarization of labour market have been diminishing jobs and stagnating wages for middle-income people.

Lax regulation concerning monopolies also contributes to growing inequality. Monopolists specialize themselves in lobbying and, consequently, have a clear path to enormous profits. An example is Walton family – six heirs to Wal-Mart empire accumulated 70$bln which is equivalent to the wealth of entire bottom 30% of US society.

Is there any solution?

In 1895 Alfred Marshall wrote that:

“highly paid labor is generally efficient and therefore not dear labor” but he admitted that “though it is full of hope for the future of human race, it will be found to exercise a very complicating influence on the theory of distribution”.

Today, so-called “efficiency wage theory” argues that how much a worker is paid affects their productivity. So increasing wages is likely to motivate workers to work more efficient and be loyal to the firm, which will benefit the firm in the long run. Perhaps that’s the way out of the vicious cycle?

Regulation is crucial in reducing inequality, most of all when it comes to services provided by financial sector, like mortgages. And it is not true that regulation adversely affects decent businesses. It was Chicago school with its laissez-faire approach who argued otherwise and people who oppose regulation – usually from the Right – still argue that regulation implies government’s superfluous interference with the market. It is true that anti-pollution regulation is bad for polluting businesses and that banning predatory lending is bad for loan sharks. But sound regulation doesn’t affect sound businesses.

Unequal distributions of gains in national income – in 2010, 93% of these gains was seized by richest 1% of Americans – suggests that if inequality is to be reduced, policy-makers have to take a careful look at alternative statistics, like median household income. The US is the most unequal country in the developed world. “Justice for all” has been displaced by “justice for those who can afford it” and American dream of going “from rags to riches” is long gone. But there is hope. Hope that the countries that used to marvel at the US won’t follow in its steps.

Nina Wieretiło